Hubris on Roller Skates (Untying Knots)

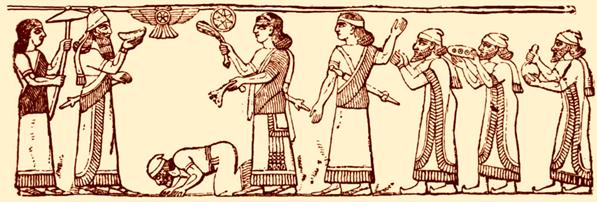

In the courts of the Assyrian kings, men of outstanding

character, ability and wisdom were prized and honored. Dian-Nisi, whose name meant

“Judge of Men,” was such a man on all counts. His name was given with definite

hubris. It was one of the titles of the Assyrian deity Shamas the “Great Judge

of All Heaven and Earth.”

I shall tell you a story of Dian-Nisi’s wisdom, foresight

and cunning, but first, I must tell you a little about knots.

*****

Over a millennium before chess was invented in India about

the 6th century AD, the Assyrians challenged each other to the tying and

untying of knots. The Bible records that Daniel, one of the children of Israel

taken captive to Assyria, had a reputation for his ability to give

interpretations, solve riddles and untie knots.

The ability to untie knots demonstrates the virtues of

wisdom, insight and patience. It reflects the persistence and thinking ability

needed to analyze and solve all manner of difficult problems. A wise teacher

can be regarded as someone able to dissolve doubts. A king’s counselor must be

able to undo or thwart the plans of others. Such a judge could be trusted with

the authority to “unbind that which was bound” by interpreting, modifying or

invalidating contracts.

Judges have often been allowed to officiate at marriage

ceremonies, where a man and women pledge to be “bound together” in the

“contract of marriage.” In some ceremonies, the wrists of the bride and groom

are physically tied together with a knot. Sometimes a sash is draped over their

wrists to symbolize that knot. Judges have also often been given the authority

to grant a divorce.

In the Jewish religious tradition, scriptures are written on

strips of parchment which are placed in small leather boxes (phylacteries) and tied

with knots to the forehead and the back of the right hand. This is an effective

public declaration of piety or “being bound to the word of God.”

Loosening a knot may not always require skill or other

virtues. There is an old story that a peasant named Gordius tied a knot that

could not be untied. An oracle prophesied that whoever could undo the knot

would become ruler of Asia. The story ends with Alexander the Great cutting the

knot with his sword. Alexander and his generals ended up conquering and ruling

large swaths of Asia and the Mediterranean basin.

*****

Now, back to our story…

Dian-Nisi understood that, in untying knots, as in all

matters of life, cheating can confer dramatic advantage in the short term, but

it is the honorable conduct of life, politics and diplomacy that yields

enduring power. Dian-Nisi was determined to be inventive and skillful, but not

stoop to cheating. He would not put his public reputation or his personal

self-respect at risk.

Dian-Nisi had a notable rival, Shimshai, in the court of his

King. Shimshai, whose name meant “sunny” was a dour, dark and jealous man,

prone to pride, scheming, lying, and back-biting. Shimshai was no fool, but his

heart did not guide him to the service of any others than himself. Dian-Nisi

consistently found himself giving counsel that directly opposed that given by

Shimshai.

Their rivalry was no secret in the Assyrian King’s court.

They had come to the point of constantly fighting like two rams. In fact the

young men in training for governorships had begun to wager on which, Dian-Nisi

or Shimshai, would lose favor with the king and be stripped of privilege, if

not his very life. Worse than that, they were beginning to align themselves with

one or the other of their King’s Viceroys.

Dian-Nisi was no fool. He realized that the young potential

governors, by splitting their loyalties between himself and his rival were not

only being divisive, but serving to diminish the honor that was due exclusively

to their King. Dian-Nisi observed that Shimshai cultivated these divisions and

rewarded loyalty given to himself. Shimshai, by too-obviously and too-clumsily

acquiring allegiance and power for himself, was becoming a threat to the King

and a target for sanction.

Likewise, the King was no fool. He did not discuss or

intervene overtly in this rivalry, but listened to both men; taking the advice

of sometimes one and sometimes the other; balancing the power and authority

that he delegated to them. Dian-Nisi wondered if his King took satisfaction

from the fight, like setting two mastiffs against each other for sport. It was

a dangerous game, but likely, not without purpose.

Dian-Nisi realized that this situation was unsustainable. He

and Shimshai both served as Seconds in the kingdom. Both held and exercised limited

but real authority to command in the name of the King. Also, both stood to be

the preeminent power behind the throne of their King’s heir. Or, perhaps, one

of them could actually become King if that heir was found to be unsuitable or

dead.

No, Dian-Nisi decided, there could not continue to be two

prime viceroys. A cart pulled in opposite directions by two oxen must break

apart. Their rivalry must inevitably rupture like boils on the face of the

Kingdom. And, the sooner Shimshai, that puss-filled cankerous corruption, was

excised, the better.

*****

Dian-Nisi’s wife waited for him at the small palace that was

their home. Dian-Nisi had been bound to her by their respective parents when he

was a young man and she had been but a small girl-child. Dian-Nisi had

eventually “tied the knot,” a little later than age and circumstances actually

permitted. Her name was Tihamtu, which means “chaos.”

Tihamtu was beautiful and vain. She adorned herself with

jewels and bright silks — strutting and fanning like a peacock — presuming to

usurp the primacy of her husbandly lord and master. She was tyrannical to the

household staff, proprietary about the appointment of her mansion and even

imperious and querulous with Dian-Nisi himself. Perhaps she aspired to become

Queen — if not soon, than sooner.

Tihamtu was a shrew. She had begun nagging Dian-Nisi for

control of the household accounts. She also reminded him that it was unbecoming

for a man of his stature to not be attended by a personal manservant. She

insisted that his favorite carpet, the one he preferred to sit on while he

smoked and meditated, be replaced and burned. In fact, Tihamtu also objected to

his using his pipe in the house and insisted that he only smoke it on the roof.

And so, as soon as his evening meal and her audience with him concluded, he

took his leave… and his carpet.

Dian-Nisi sat on his roof this night, smoking his favorite

pipe on his favorite carpet in his favorite corner. He contemplated the stars

above and their omens. He contemplated the neighbors below and their petty

squabbles. He contemplated the burdens of his King, the machinations of his

rival and the grievousness of his wife.

No, Dian-Nisi decided, he could not continue to be opposed

in his own home. That, too, was unsustainable. He reflected, with guarded

amusement, that his marriage to Tihamtu was like a knot. But, it would not be

honorable to cut this knot, as with a knife. It would be necessary to untie it

properly, with understanding, finesse and patience.

And, having made his decision, Dian-Nisi called for a scribe

and dictated that (1) Tihamtu be given responsibility for the household

accounts, (2) an excavation be made under a tile in her chamber to safely

conceal the funds at her disposal, (3) a new carpet be commissioned for the

guest hall and (4) personal manservants be vetted and brought for him to

interview until such time as he approved and appointed one.

At about this point, waxing philosophical about the nature

of knotty problems, Dian-Nisi had the profound realization that untying was

only the tail of the beast. It was the tying that empowered the jaws to bite

and the teeth to hold. He began setting aside time to think about new kinds of

knots.

*****

In the King’s court, an important issue came to a head. It

involved several core differences in the way the King’s empire was to be

administered. It was the day after a full moon and considered a propitious time

to address major issues.

In the King’s court, an important issue came to a head. It

involved several core differences in the way the King’s empire was to be

administered. It was the day after a full moon and considered a propitious time

to address major issues.

Shimshai told his King that all Territorial Administrators

and Magistrates must bow down to their God Marduk or suffer death. Dian-Nisi

advised his King that these functionaries need only be required to perform with

loyalty to their King and that, should they find favor in the eyes of the

foreign gods of their youth, this could only improve the quality of their

service.

Shimshai told his King that, in the future, all the

able-bodied males of newly-conquered territories should be castrated and

consigned as slaves. Dian-Nisi advised his King that deprived of their men,

conquered women would certainly fill the hearts of their children with hatred

for the King, which would slowly undermine the Kingdom. And so it went.

The King retired to his chambers immediately after that

confrontation with no comment—except to command that both men withdraw from his

face, and each other, until the morning after the next full moon when they were

to attend him in a private audience.

Very little changed for Dian-Nisi during that month. He

still served at the palace, as before, except not before the King himself.

Dian-Nisi spent a large part of his time instructing his young men in the

higher arts of discrimination, judgment, political strategy, and ethics. He did

not speak to Shimshai or to the young men that attended Shimshai. Likewise,

Shimshai absented himself from the inner court and spent his time conspiring

with his acolytes.

Dian-Nisi came home regularly each night. He still took supper

and, when the weather permitted, he retired to his roof to smoke, meditate and

practice a new kind of knot. He changed his mind about waiting for a

commissioned carpet and directed that Tihamtu select an already-completed one

such as she might desire.

He also delegated to his wife the selection of his new

manservant. She chose a younger man who radiated the strength and confidence of

virility. The household whispered their suspicions, but Dian-Nisi approved her

choice without hesitation. In fact, Dian-Nisi confided to his wife that he had

been indulging her concern for the appearance of his status but that he really

had little use for the fellow’s personal service. She should therefore consider

putting him to tasks within the household as she saw fit.

*****

The critical day after the next full moon arrived. Dian-Nisi

and Shimshai waited together silently in one of the King’s antechambers. Shimshai

eyed Dian-Nisi with hostility but was rewarded with only closed eyes and a

comfortable smile in return. At last, they were summoned to attend their King

together.

The King advised them both that their contrary opinions were

a tribulation and affliction to him. He commanded that first Shimshai and then

Dian-Nisi advise him on how their differences might best be resolved.

Shimshai spoke from his heart. “This inadequate man,

Dian-Nishi, is worthless to you. He is weak and so is his advice. His

commitment to our God Marduk is incomplete and impure. He coddles our enemies

and hesitates to act in strength. He promotes a promiscuous drain on our

treasury by encouraging the poor to become dependent on your open hand. You

must annihilate this traitor, his family and the young men who have gathered to

him. You must purge them from your face, your Kingdom, and this earth.”

Dian-Nisi spoke from his head. “This selfish and ambitious

man has set himself as a rival for Your throne. Nonetheless, You will deal with

us both as You see fit — perhaps with mercy — perhaps with justice. If you so

will it, put us before the eyes of your entire court and have the young men

divide themselves between those loyal to Shimshai, those loyal to myself and

those who prefer to not declare a loyalty. Let us both be given a three-cubit

length of cord and a quarter part of the day in which to knot it as we will.

Let us exchange our cords and attempt to untie the other’s knot. In this way,

You may then see that which You wish to know and act in the manner You wish to

act. At the conclusion, all eyes will see that You act in wisdom and govern in

uprightness and power.”

The King spoke from necessity and political expediency. “As

you both have spoken, I shall do. Let the cords and the times be given. Let the

tying and the separating of the young men occur in private antechambers under

the eyes of my guards. Let the untying occur under the eyes of all. However,

just as Shimshai has spoken, the loser will not be looked upon with favor.

Beyond this, I shall decide as I will and it shall be done as I command.”

And so, the inquisition by trial was decreed. Both men, with

their supporters, were placed in separate rooms to tie and then presented

before the assembly to untie — with the future of themselves, their families,

their acolytes, and the Kingdom, in the balance.

Dian-Nisi did not begin tying a conventional knot but

prepared his cord in a way that had never been seen before. He tied a series of

simple overhand knots at seemingly-irregular intervals down its length. Then,

he summoned a brass basin and piled the cord loosely inside. He directed his

young men to form a circle and spit into the bowl until the cord was thoroughly

wetted. He looped the cord once around the central pillar of the room, tied the

ends together temporarily and pulled the string of knots tightly until the cord

thought that it must burst and the knots wept tears of grief.

Dian-Nisi began weaving a tight ball. He did not bury the

ends inside, but left them free to tease and torment. The series of small knots

became knuckles that interlaced with each other, prohibiting any possible slack

from making room to pull a loose end through. Occasionally, he twisted the cord

to take up some slight extra distance between knuckles.

Finishing his masterpiece of invention, Dian-Nisi strained

to roll the last section of knuckles tightly into the holes waiting in the

layer beneath. At the last, he held the ball by the protruding ends and rotated

it above the coals of the brazier that warmed the room. As the spittle slowly

evaporated, the fibers of the cord tightened even more and the mucus bound its

strands together.

At the appointed time, the men presented their knots to

their King who inspected and returned them, each man’s to the other. He

directed his scribes to attend and he spoke:

“Shimshai, your work is tight and well-made; it is a thing

of beauty. But, it is a pattern that was known to my father’s father. Your mind

is bound to the past.

“Dian-Nisi, your work is tight and well-made. In fact, it is

a thing of wonder. Your mind is bound to the future and able to solve problems

where others fail to even take notice. If I were to indulge myself, I would

keep both knots, intact, and display them in a place of honor.

“Shimshai, your service is of no further use to me. Yet, I

give you three options. If you concede now, you must remove yourself and your

family to a far land. I must never again see your face, hear your name or be

troubled by your memory. If you attempt and succeed, you must be exiled in your

own house, but able to enjoy the possessions that you have accumulated until

this time. If you attempt and fail, you shall be opened up, your entrails

spilled upon the ground, your head placed in shame upon a pole in the public

market and the males of your family taken to a departing caravan and sold into

slavery.” Shimshai conceded.

The King called for his scribes to begin a new record.

“Dian-Nisi, I trust that you would withhold nothing that I ask. Yet, I require

your continuing devoted service.” The King removed his seal ring, beckoned

Dian-Nisi forward and placed it on his finger. “I grow tired of intervening in

the affairs of fools. Dian-Nisi, for as long as I may continue in this choice,

I authorize you to bind in my name and to judge in my name. Only my household

and my throne do I reserve from your hand.” With that, the King rose up, took

the two knots for himself and left the room with his personal attendants.

*****

That very evening, upon returning home, Dian-Nisi found that

his entire household staff was in an uproar. The house’s head servant reported

that Tihamtu had departed in a hired cart and had not returned. Also, there was

an empty hole in the floor of her bed chamber. And, to make matters worse, his

manservant had left to purchase the expensive new carpet for the guest hall and

had also never returned.

Although the rest of the household was upset, Dian-Nisi

simply called for his pipe, sat on his accustomed carpet and smoked contentedly

as he reflected on his victory over Shimshai and on how little his wife and

manservant would be missed. Dian-Nisi congratulated himself on untying two

difficult knots on the same day. Only then did it occur to him that he would be

expected to select his own counselors, find a new wife and begin accepting

concubines as gifts.

David Satterlee

No comments:

Post a Comment